I. Summary and introduction

Small Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) are proving to be a key component of coastal ocean observing systems, providing unique data sets at shallow depths and over shelf seas. This paper describes how the use of micro-AUVs improves the sampling and study of coastal areas under the influence of river plumes, as well as their advantages and limitations. Two YUCO-CTD micro-AUVs developed by the Seaber company have been deployed in these coastal river plume areas along the french coast since 2022 in the framework of the innovative MICO project and the research PPR RiOMar project. Data processing and plotting tools have been developed in Python and are freely available to the scientific community. Micro-AUVs are able to catch frontal structures and oceanic variability at small scales. They provide an interesting spatialization tool in the framework of augmented observations. Best practices for the deployment of these micro-AUVs are given, including optimal speed of 2 m.s-1, ballast strategy in variable salinity areas, launching and recovery from different boats and the way to mimic a profiling probe. Future improvements to these systems to meet the needs of the scientific community include the addition of sensors (to measure ocean currents and biogeochemical parameters) and navigation capabilities to monitor changes ranging from extreme events to global ocean warming.

Introduction

🌊 Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) were first developed for marine geoscience purposes in the 1980s [1]. Since the 2000s, AUVs have been successfully and intensively deployed in the deep ocean to provide seafloor mapping [2], even in extreme environments such as the deepest hydrothermal fields ( [3]; [4]). The underwater drones were then equipped with water quality monitoring instruments such as cameras, Funded by MICO Innovative project (R´egion Bretagne), PPR RiOMar (ANR-22-POCE-0006) and State-Region Plan Contract ObsOcean – ROECILICO multi-parameter probes, and optical sensors for turbidity and chlorophyll-a measurements. They are now widely used in the scientific, defense, oil and gas, and policy sectors. Although the first AUVs, a few meters long, were not tied to the vessel and did not require direct human control while collecting data, these autonomous systems were typically deployed from a research vessel and were followed during their dives. Their autonomous nature was reduced. Smaller AUVs dedicated to sample the coastal zone have been developed in the last 15 years [5], offering easy deployment and recovery even from rigid inflatable boats, with limited human resources and cost, but reduced battery capacity. Taking advantage of the miniaturization of systems, the miniaturization of scientific sensors and the emergence of lowtech systems, micro-AUVs of less than 1 m in length and weighing around 10 kg have been developed over the last decade. With operating depths of around 300 m and 8-10 hours of autonomy, they are suitable for coastal and shelf sea monitoring and allow multi-AUV operations. Micro-AUVs can be used for the measurement of water parameters in coastal environments over the continental shelf, which is essential to understand and monitor the evolution of our oceans in the short, medium and long terms. For the latest, repetitive field surveys are needed. This is done by measuring temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen concentration and turbidity with a spatial coverage that captures the variability of the dynamics of these coastal zones, which are influenced by factors such as wind, waves, currents, tides and depth variations. In riverine coastal areas facing climate change and anthropogenic input, the impacts of extreme events such as storms, floods, and heat waves on the physics and ecosystems are not fully understood [6]. One reason for this is the difficulty of sampling the ocean during these events, e.g. ships cannot operate during storms, and to obtain adequate spatial coverage to synoptically characterize the 3D structures. Gliders are capable of sampling over long distances even under strong sea conditions, but they operate only at depths greater than 30 m and do not provide an instantaneous picture of the water column. Micro-AUVs are very complementary, as they can operate in the coastal zone between 5 and 30 m depth and provide a more synoptic view at greater depths. In this study, our focus is on the use of micro-AUVs in the framework of the building of future augmented observatories in river-influenced areas along the French coast. A novel observation strategy is foreseen to anticipate the future of coastal water quality (primary production, oxygenation, acidification, eutrophication, contamination, harmful algae). Augmented observatories will go beyond the existing observation networks within the French ILICO research infrastructure by densifying and spatializing data obtained at fixed stations. This will be achieved through the use of autonomous and mobile devices, with micro-AUVs complementing gliders, fixed stations, lowtech systems, and satellites. Deployments of two YUCO micro-AUVs equipped with a Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) sensor and a turbidimeter or a dissolved oxygen concentration sensor have been carried out in coastal areas influenced by rivers along the French coast in the framework of the MICO and PPR RiOMar projects. Recommendations on the drone autonomy, speed and navigation modes (sawtooth, fixed altitude or depth) could be derived. Sensor data processing and visualization tools were developed and made available to the community. The ability of micro-AUVs equipped with a DVL (Doppler Velocity Log) to dive in different environments, from the tidally driven Bay of Brest to the Rhone River delta, which is mainly forced by the wind and river inflow, was validated. The strategy of multi-AUV deployment has also been explored. Finally, a micro-AUV experiment made it possible to estimate

the representativeness of the bottom long-term hydrological mooring in the Bay of Vilaine.

II. Materials and methods

The surveys were carried out using two YUCO Seaber micro-AUVs in the YUCO-CTD configuration.

Description of the AUVs

The YUCO-CTD is a micro-AUV developed by the Seaber company for high-resolution oceanographic data collection in coastal and open-water environments. Measuring approximately 1.1 meters in length and weighing approximately 10 kg in air, it can be operated by a single user. Its hydrodynamic shape and efficient propulsion system enable navigation at speeds of up to 3 knots, with a typical endurance of up to 10 hours at 2.5 knots, depending on mission parameters. It can operate at depths of up to 300 meters. Its navigation system combines inertial and acoustic positioning (Doppler Velocity Logger), ensuring trajectory control and data georeferencing. The YUCO has real-time communication capabilities when emerged, allowing efficient mission planning and control using the Seaplan software provided by the manufacturer. Both YUCO-CTDs used in this study are equipped with a high precision Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) probe from RBR (Legato3 – https://rbr-global.com/products/ctdgliders auvs/rbrlegato/). The acquired data can be easily downloaded in CSV format via a WiFi connection after each deployment. For power management efficiency, the CTD sensors sample at a rate of 2Hz. The temperature channel is calibrated with an accuracy of ± 0.002°C (ITS-90 scale) over the range of -5 to +35 °C, with a time constant of less than 1 s. The accuracy of the pressure channel is 0.05% of the full scale rating (1000 m) and the resolution is 0.001%. The conductivity channel is calibrated with an accuracy of ± 0.003 mS.cm-1 over the range 0 to 85 mS.cm-1. In addition, one of the YUCO-CTD is equipped with a Turner Design Cyclops-7F turbidity sensor (accuracy 10% in the range of 0 to 500 NTU, resolution 0.1 NTU) with a time constant of 0.1 s, and will be referred to as YUCO-TURB. The other, hereafter referred to as YUCO-OXYG, is equipped with an RBRcoda T.ODO fast oxygen sensor, which has an accuracy of ±5% over 0 to 120% range, stable performance between 1.5°C and 30°C, and a time constant of approximately 1 s. Finally, the YUCO-CTDs are equipped with a WaterLinked A50 DVL (Performance version) at 1 kHz frequency, which offers a velocity resolution of 0.1 mm.s-1, a long term accuracy of ±0.1%, that can operate for a maximum altitude of 35-50 meters above bottom depending on environmental conditions.

Description of the experiments

Several experiments were conducted over three years. The first series of tests aimed to evaluate the YUCO’s navigation capabilities, including rail navigation, waypoint targeting, and segment-based navigation (time- or distance-based), under various hydrological conditions. These tests were conducted in close collaboration with the Seaber development team. Different launch methods were implemented to assess the feasibility of the deployment. In addition, various transect modes were tested, such as navigation at constant depth below the sea surface or above the seabed, or sawtooth profile ensuring smooth transitions between the surface and the bottom. Eventually, the data acquired by the CTD sensors

were compared with classic CTD profiles performed in-situ with the same sensors (RBR Maestro CTD profiler). The trials were primarily carried out from a light rigid inflatable boat,

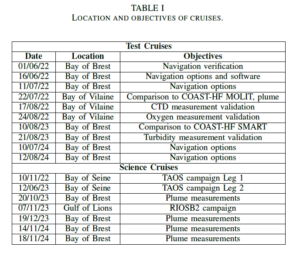

mainly in Brittany. Once the tests were validated in a specific software version, the YUCOs were deployed to achieve scientific objectives in areas affected by rivers. However, whenever a new feature was added or a behavior change occurred, additional experiments were conducted to execute previously validated missions to ensure continuity of development. Three areas with several science campaigns can be distinguished: the Bay of Brest (semi-enclosed area, high tidal mixing – rigid inflatable boat); the Bay of Seine (river plume, very high tidal mixing – rigid inflatable boat) and the Gulf of Lions (river plume, no tidal mixing – oceanographic ship). The main campaigns dedicated to technical or science issues are listed in table I. The first campaigns in 2022 were dedicated to validating the navigation fo the AUVs and the sensors functioning. Then, validation of the physical parameters measured by the CTD and its associated sensors was performed by comparing the data with those measured at the stations of the COAST-HF national observation network (MOLIT and SMART stations). Campaigns in the Bay of Brest, Bay of Seine, Bay of Vilaine and in the Gulf of Lions-Rhone area were dedicated to the study of areas impacted by river plume.

Data processing

The AUV real time computed navigation is contaminated by errors (poor magnetic heading, AUV drift due to ocean currents, poor drone velocity estimation when no bottom tracking, poor bottom tracking detection). The Seaplan software by Seaber enables one to analyze the dives a posteriori and

provides a corrected trajectory based on the inertial central outputs and the GPS locations. A Python library code was developed to process and analyze the environmental data collected by the YUCOs during their missions. The entire library with examples of notebooks and Python scripts is available at https://github.com/plouf40/YUCO data explorer.git. Raw data from CSV files are read with the Pandas library and filtered to retain only valid mission data. Then, the main program calculates the distance traveled by the AUV using the Haversine function and combines altitude and depth information to compute bathymetry. It also supports concatenating multiple mission datasets, updating the cumulative distance, and merging the data into a single unified dataset. This part of the library has been designed to cover all types of YUCOs (e.g. CTD, PHYSICO for water quality, SideScan, e-DNA). Once the mission data are processed, for the YUCO-CTD

series, various calculations are applied to derive key oceanographic parameters thanks to the TEOS-10 library, including conservative temperature, absolute salinity, and density, and the data are stored in the DataFrame. A first quality check is performed to remove any spurious measurements. For the YUCO-OXYG, oxygen data are recomputed based on the phase signal to account for the temperature measured by the Legato3 sensor and not the one from the T.ODO sensor, which is not fast enough and comes with a lower resolution. Both compensated oxygen concentration and saturation values are corrected in the final dataset. A generic visualization function is available to automatically generate depth-related plots (or along-track related plots) for each AUV mission data, displaying environmental variables like temperature, salinity, density, oxygen saturation, and turbidity. The user can choose to visualize bathymetry, map projections, and missions either separately or combined. The function also creates a Temperature-Salinity diagram scattered with depth data and a 2D geographic map with an option to overlay SIG (Spatial Information Georeferencing) layers based on the user’s selection. Plots are saved as images, with custom x-axes for time or distance, and high-quality figures are produced for further analysis or publication.

III. Validation of the Yuco-CTD Mesurements in the bay of Brest

Effects of the YUCO-CTD diving patterns on CTD measurements

On October 20, 2023, two radials were sampled in the Bay of Brest at ebb tide, and a SWIFT Valeport CTD was taken on board for comparison with the AUV measurements. The northern radial was used to check the YUCO’s behavior in this area with highly variable bathymetry (from 10 to 30 m depth). The second and longer route was taken to test the sensors and try to observe differences in the canyon environment. Eleven dives are usable, at constant depth, constant altitude and along

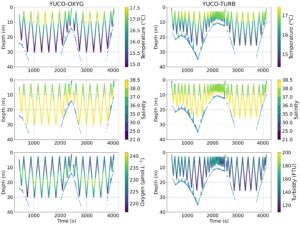

sawtooth. During sawtooth dives, vertical descent and ascent speeds of 0.1 to 0.3 m.s-1 were tested. Increasing the vertical speed results in tighter sawtooths and therefore better spatial sampling along the radial. A speed of 0.3 m.s-1 was then maintained, higher velocities resulting in difficulties to handle the limits of maximum and minimum depths. The turns at the bottom and surface are made by overshooting. During the 8-minute profiles, the YUCO-CTDs consumed approximately 2% of the battery, regardless of whether they were navigating horizontally or in a sawtooth pattern, and regardless of the vertical speed programmed in the latter case. Measurements for dives at constant depths of 2 m and 5 m, dives at constant altitudes of 6 m and 7 m above the seafloor and sawtooth dives with different ascent rates were compared for the YUCO-OXYG (not shown). The measurement patterns of the sawtooth dives are consistent with each other, regardless of vertical ascent rate. Regarding the temperature values, there was overall consistency, with values varying by up to 0.02°C at certain longitudes. The same behavior is observed for salinity, with deviations of up to 0.02. Finally, oxygen concentration measurements are noisier, with deviations of up to 4 μmol.L-1, which can be explained by the greater variability of this parameter over time and space. Similar comparisons were made for the YUCO-TURB (not shown). Although the conclusions were similar for the parameters measured by the CTD, the difference in salinity was greater (up to 0.05) and a much greater variability in turbidity was observed, with a difference of 30 to 50 FTU between the values measured during sawtooth dives and those during constant depth dives, at the same longitude and depth Fig. 3. Behavior and measurements for dives with the YUCO-OXYG (orange line for the bottom track) and the YUCO-TURB (blue line for the bottom track) along a similar radial on October 20, 2023. (6 m above the bottom or 5 m below the surface). Given the difference in salinity between sawtooth dives and dives at constant depth or altitude, it is likely that hydrological conditions have evolved between dives, explaining these differences and making comparisons very difficult with a YUCO-TURB under these environmental conditions.

Cross comparisons between the YUCO-OXYG and the YUCO-TURB

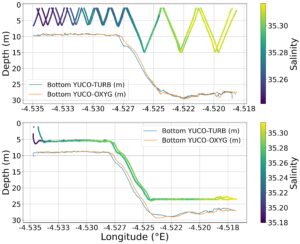

During the same campaign in October 2023, both micro- AUVs were launched simultaneously with the same missions. It was therefore possible to compare their behavior and the

values of the parameters measured for three sawtooth dives and one dive at constant depth (Fig. 3). The sawtooth profiles show a slight spatial (and temporal) shift, whereas the profiles at constant altitude overlap. The depth of the seabed as seen by the two devices is equivalent for all dives. A salinity bias of around 0.01 was found for each comparison, probably due to a drift from factory sensor calibration, although this value remains low for coastal measurements in river plume areas. This comparison shows consistency in the data acquired by the two micro-AUVs, and the possibility of using either of them for CTD measurements.

Comparison of CTD measurements using the YUCO-CTD and a profiling probe

On November 18, 2024, a long sawtooth radial was carriedout along the Aulne River (Bay of Brest) to validate both the navigation parameters and the CTD measurements. Along

the transect, manual profiles were regularly acquired using an RBR Maestro CTD (roughly every 1 km). Fig. 4 presents the temperature and salinity variations recorded by the YUCOTURB along the transect, overlaid with manual CTD cast measurements for reference. The temperature data show strong agreement between the YUCO-TURB and the RBR Maestro profiles, with variations closely following the same trends throughout the water column. The sawtooth pattern allows for a high spatial resolution of temperature gradients, particularly in the upper layers where the influence of surface mixing is more pronounced. Salinity measurements also exhibit a consistent pattern between both instruments, with the YUCOTURB accurately capturing the stratification present in the water column. Minor discrepancies are observed mainly at the turning points of the YUCO. It can be attributed to short-term sensor response times or slight positioning offsets between the AUV and the manual cast. Overall, the comparison confirms the reliability of the YUCO measurements, demonstrating its ability to capture fine-scale oceanographic structures with a resolution comparable to standard CTD profiling instruments.

IV. Observing River Plumes using the MICRO-AUVs

📈 Contrasted areas, in terms of river discharge and tidal forcing, were sampled (Fig. 2). Results obtained in the Bay of Brest, the Bay of Vilaine and the Gulf of Lions are discussed.

Influence of a small river in a tidal area : the Bay of Brest

In the Bay of Brest, a series of deployments were carried out to assess the ability of the YUCO to resolve fine-scale river plume dynamics in a strongly tidal environment. This

bay presents complex hydrodynamics, where freshwater inputs from small rivers interact with intense tidal mixing. As already shown in the previous section, this kind of transects highlights the YUCO’s added value to a classic oceanographic cruise in terms of spatial resolution and threedimensional representation of hydrographic structures. During the last cruise, the two AUVs were deployed, with the YUCOOXYG performing a near-surface zigzag (not shown) and the YUCO-TURB conducting deeper profiles. This made it possible to capture both horizontal and vertical gradients of temperature and salinity with unprecedented details. This highresolution coverage enables a quasi-3D reconstruction of the

plume dynamics, particularly in the surface layer where lateral gradients are the strongest.

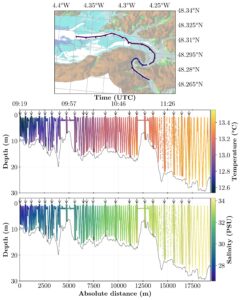

In the same way, two coordinated transects performed on December 19, 2023, using both YUCOs simultaneously and navigating in parallel separated by 250 meters, revealed the position and structure of the central tidal eddy during flood tide (Fig.5). This well-known tide-driven eddy remains difficult to observe in terms of spatial footprint, due to military

restrictions, dense vessel traffic, and limitations for the use of remotely sensed observations (high cloud cover and low revisit frequency of high-resolution SST imagery). The sea surface temperature field extracted from the MARS3D model provided valuable context for interpreting the in-situ observations. The salinity and temperature time series observed by the YUCOs clearly reveal strong lateral gradients across the transect, associated with the outflow of riverine waters from the Aulne River and the tidal eddy circulation during flood tide. These gradients are consistent with the modeled sea surface temperature distribution and appear even sharper than those suggested by the model. The spatial offset between gradient of both transects provides valuable insight for evaluating and refining model performance. Subsequent missions were carried out next to the narrow strait connecting the Bay to the open ocean (the ”Goulet”), aiming to identify the propagation path of plumes. However, these experiments emphasized the importance of adapting the navigation strategy relatively to the current regime, which can be strong (> 2 m.s-1): the user should consider increasing the safety timeout for each programming step or aiming to deploy the AUV in the same direction as currents.

Deployments in deeper regions to sample the Rhone River plume in the micro-tidal Gulf of Lions

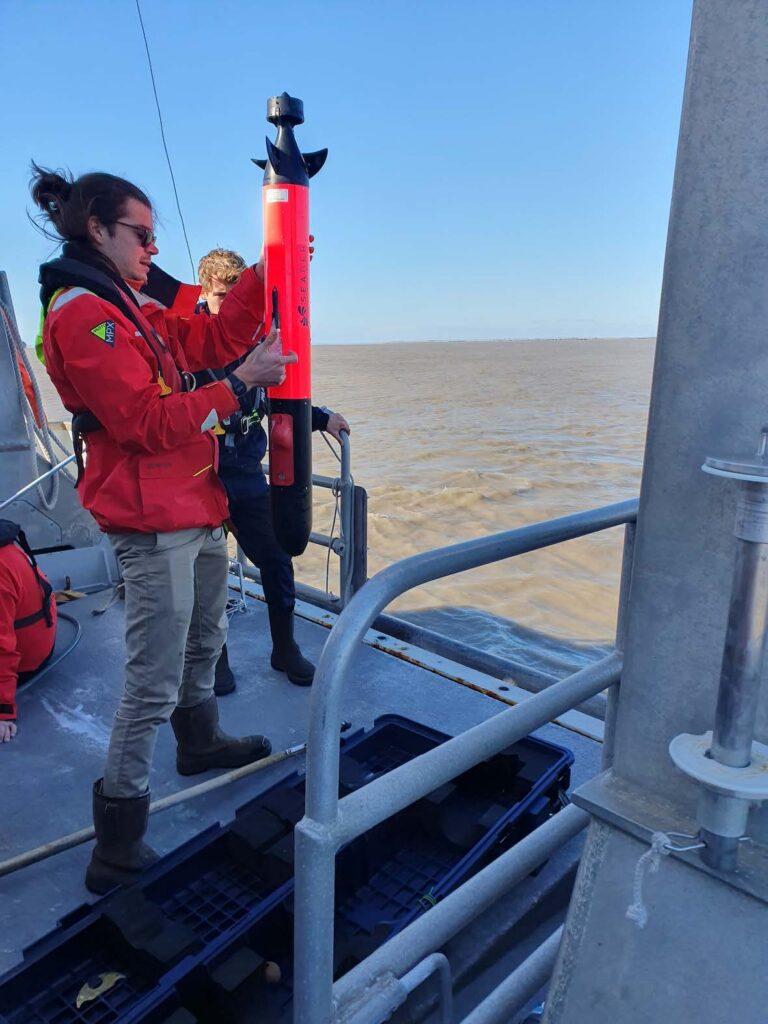

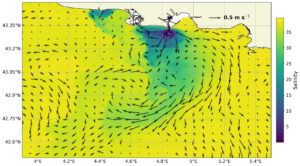

An opportunity to deploy the YUCOs from the coastal vessel Ant´edon 2 arose during the RioSB2 campaign (November 7–8, 2023), conducted as part of the PPR RiOMar project,

which focuses on observing and anticipating the evolution of river-dominated ocean margins in the 21st century. The aim was both to test deployments and, above all, recovery from this type of vessel, which is higher in water than rigid inflatable boats (Fig. 1), and also to carry out radials in the Rhone River prodelta zone in order to characterize the vertical extension of the plume during the campaign. Tests and calibration of the micro-AUVs were performed on November 7 and two longer

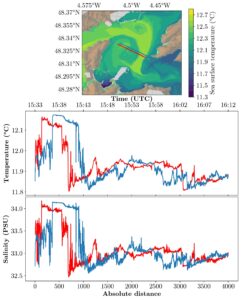

deployments were carried out on November 8 (Fig. 6) under more favorable sea conditions. The sea surface water was turbid (Fig. 1), associated with the presence of the Rhone River plume. Indeed, successive floods of the Rhone were identified during the previous days, with a flow exceeding 4000 m3.s-1 on November 6, allowing

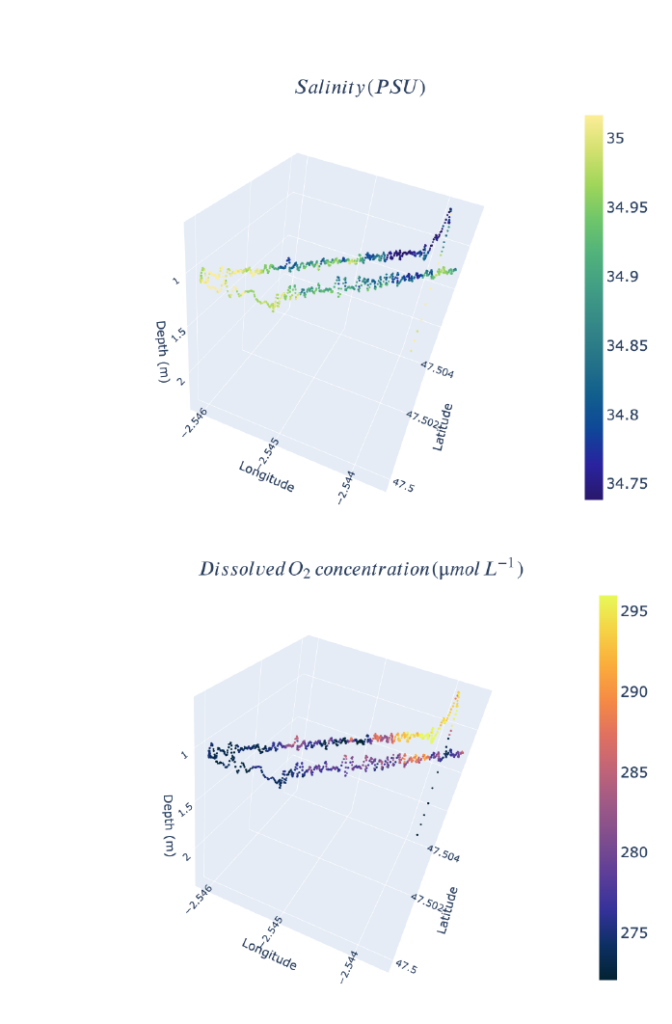

one to sample an exceptional situation. The surface plume was well developed according to Ifremer’s MARS3D-MENOR model forecasts (Fig. 7), so the YUCOs remained within the zone of influence during their deployment. On November 7, a ballast test was carried out by attaching the YUCO to the stern of the boat using a rope. As the latter floated poorly, a wedge was removed to adapt the drone’s buoyancy, which floated correctly at the end of this operation. The recovery method was then tested at the end of the dive

at constant depth, using a gaff adapted by our laboratory for this purpose from the side of the boat, thus validating the technique. On November 8, each drone completed two round trips to and from the MesuRho station (Fig. 6 and Fig. 8), performing a surfacing maneuver to acquire a GPS signal before resuming its mission. Upon completion of their tasks, the drones drifted briefly before being retrieved. As shown by a CTD profile taken near the mouth (not shown), the plume thickness in this area is around 2 m, with a salinity of around 31.5. Salinity then increases rapidly to a depth of 4 m, where values of more than 38 are representative of Mediterranean water. The plume is also characterized by colder water at the surface (approximately 16.2°C) compared to the surrounding area, along with elevated fluorescence levels, and a distinct dissolved oxygen profile: concentrations peak at 5.5 ml·L-1 at the surface, decrease to around 5 ml·L-1 at a depth of 4 m, rise again near 15 m, and then gradually decrease. From this experiment, the YUCO dives give us 2D spatialized information and allow us to assess the spatial variability of the plume away from the mouth and at depth (Fig. 8). Overall, the extreme values seen by the CTD in temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen concentrations are linked to the presence of the plume in the first two meters below the surface when the micro-AUV dives or resurfaces. In the next 10-15 meters along the water column, the water is warmer and less salty (the closer you get to the mouth), with low oxygen concentrations and a higher turbidity as approaching the river mouth. This is a plume dilution zone. Below, the water is colder, saltier, more oxygenated over 10-15m depth and less turbid. The particular conditions of this environment (many particles in the plume in the upper layer of the sea, and far fewer in the underlying part characteristic of Mediterranean waters, followed by a muddy bottom) have an impact on the DVL’s ability to see the bottom. The YUCO’s DVL tends to lose sight of the seafloor during sawtooth dives, when the seafloor is more than 15-20 m below the micro-AUV, and depending on its inclination.

Study of the represntativeness of fixed stations using the YUCOs in the Bay of Vilaine

Two campaigns were carried out in the Bay of Vilaine between July and August 2022. During the first series of dives, the YUCO collided with the MOLIT buoy (from the COASTHF

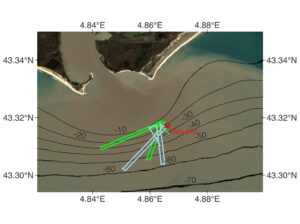

National Observation Service [8]). The YUCO’s nose was broken and the laptop on board took on water. Fig. 9 shows only the second campaign on August 24, 2022. Six dives were carried out on round trips of 1 to 2 km at a speed of 2 m.s-1 and at a constant depth of 2.5 m below the surface, except for the section closest to the Vilaine River (starting at the ’M’ location on the plot of Fig 9), which was at a constant depth of 1 m below the surface due to the shallower depths and the heavy shipping traffic in the area.

The summer of 2022 is characterized by a series of heatwaves. On August 24, the flow of the Vilaine River was low, around 0.3 m3.s-1. Fig. 9 shows the measurements recorded by the YUCO-OXYG. Temperatures are above 20°C at the coast, in shallow waters, which is consistent with what is modeled in most of the bays in the area at this period (modeled fields available on https://marc.ifremer.fr/), with a measured maximum of 22°C close to the surface. Salinities show an inverse trend, being lower along the coast and near the mouth of the Vilaine River (northeast of the plot), particularly close to the surface and thus to the diluted waters from the river. Dissolved oxygen concentrations are the highest near the coast and toward the surface, in line with high primary production. We zoomed in on the north-east radial, the closest to the

mouth of the Vilaine River. Fig. 10 illustrates the variability of parameters measured over a distance of about 1 km from the launch site. Salinity and dissolved oxygen concentrations show a high degree of variability along the coast-to-large round trip, with lower salinity values at the beginning and at the end of the dive, and higher oxygen concentration values at the beginning of the dive. Different water masses are encountered during the dive, with a likely freshwater inflow from the coast or a harbor influencing the launch area. Since a bottom monitoring station for continuous dissolved oxygen measurement was positioned at station ’M’, close to the launching point, the measurements taken with the YUCO allow us to illustrate their usefulness here by showing that the monitoring station represents only local variability and is not representative of the extended zone.

V.Use of micro-AUVs : limitations and benefits

Benefits

From the various experiments and deployment conditions, several benefits of using micro-AUVs for the observation of the coastal zones have been identified. As far as technical issues are concerned, the YUCO micro- AUV is easy to launch in open water, even from small boats and by a single human. Such micro-AUVs allow sampling in very shallow waters (less than 30 m depth) and complement the autonomous ocean sampling capabilities of other existing autonomous platforms (e.g. gliders). As a micro- AUV, it comes with an affordable price that allows for multideployments or deployment in risky areas of the coastal seas. We provided a lot of feedback to the Seaber company to make the AUV meet the needs of the scientist non-roboticist community : launching from all sizes of boats, easy programming features, underwater behavior adapted to usual sampling strategies, as well as post-cruise corrected trajectory availability. The YUCO can now be programmed while surfacing, eliminating the need to bring it back to the boat between missions. Thanks to planning software improvements, the YUCO is easy to program, as the Seaplan software now includes mapping with bathymetry and provides in real time the mission duration

and battery use given the mission features. When a mission is loaded once, no action is needed to start it again. The YUCO offers various types of navigation: at a given depth below the surface or above the seabed, between the deepest and the shallowest points along sawtooths at chosen vertical velocity, and helical descent to mimic profiling with a turning radius of 10 m. The stability of the system underwater allows for good sampling with the YUCO-CTD version. The community software, developed by the scientific teams and freely available in open repositories, ensures the future evolution of the mission and scientific data processing, including the potential addition of sensors.

Limitations

The mission planning time estimation can be underestimated due to the intense currents encountered during the dive, which are not taken into account during the computation. The dive can even be aborted if the difference between planned dive time and real time is too large. This is the case for routes against strong currents in tidal areas.

In its actual configuration, the YUCO is not intended for longduration deployments (more than 1-2 hours) without surfacing, due to the quality of the positioning and to possible surfacing during the dive associated with the limited range of the remote unit. Indeed, the SEACOMM UHF handheld command unit allows one to locate the YUCO up to a distance of 2 km, which can be upgraded to 5 km with a special antenna. In clear or muddy waters, the DVL can have a reduced range (less than 30 m above the bottom), and the navigation system loses its bottom tracking ability, resulting in navigation errors and missing information. Due to the time response of the sensors in this configuration using a CTD, the maximum speed is limited to 2 m.s-1 even if the YUCO can reach up to 3 m.s-1. At a speed of 2 m.s-1, the autonomy is given to be 6 hours and 10 hours for 1.5 m.s-1. However, we were not able to go to the limit during daily campaigns, as other constraints were stronger (i.e. computer battery, tidal cycle, distance from the harbor). Finally, the

YUCO cannot be deployed from a beach, which would make it truly unmanned, mainly due to complex recovery issues. These limitations are mainly related to the technical capabilities of the existing and commercialized YUCO. The developers are constantly working to overcome these limitations.

Best practices

A number of recommendations for the YUCO deployment parameters, mission planning and deployment techniques emerged from the various experiments. When deployed in waters of variable salinity (river mouths and plumes), the drone’s ballast must be adjusted. Always place the YUCO in the least salty water of the dive site to test

the ballast. Then a magnetic calibration should be performed. Launching from a rigid inflatable boat can be done in two ways. For new users, it is easier to accompany the YUCO in

water and wait for it to move than to launch it from a standing position because of the difficulty of orienting the drone at 45° and of the remaining air in the head. For recovery, we did not use the ”come-back-to-me” order, but rather came with the boat to prevent collisions. From a rigid inflatable boat, the operation consists of retrieving the AUV by hand. From a coastal boat higher in the water, launching has to be done while powering off the engines and the direction is correctly set up to avoid collision with the boat propeller and bottom. Note that collisions are favored by the size of the boat. Recovery is made easier and safer by using a gaff, and by the side of the boat instead of the stern, where the micro-AUV risks being caught up in the propeller. The deployment parameters (micro-AUV velocity, deployment time, maximum and minimum depths) have to be adapted

to the deployment area. Attention must be paid to the tidal cycle in tidal areas to adapt the minimum/maximum depths during sawtooth dives and to choose appropriate routes to avoid surfacing of the micro-AUV due to a large countercurrent that would slow down the drone. In known obstacle-free areas, navigation down to 1 m above bottom is possible, but in unknown areas, or where wrecks or rocks are present, this value has to be set to 2 to 5 meters above bottom. A minimum navigation depth of 1 m below the surface is required during sawtooths to avoid surfacing, which must be set to 2 m if boats are located around the diving area. As mentioned above, the maximum speed must be set to 2 m.s-1 for quality CTD measurements. This is also the velocity which is best suited to measurements at sea, allowing good data over the longest distance. When performing a sawtooth transect, the vertical speed must be set to a maximum of 0.3 m·s-1 in the software to prevent unintended surfacing, bottom contact, or mission abort, especially when descending where the bathymetry is higher than the predefined lower limit of the transect. When helically ascending from a near-bottom dive, a speed of 0.6 m.s-1 is recommended, to exit as close to the bottom location as possible at the end of the dive. This will ensure a good post-process of the navigation. To achieve the equivalent of a CTD profile with the YUCO, one needs to select helical descent, then ”float” mode to switch off the motor, allowing the YUCO to rise almost vertically. The environment affects the DVL range, which is used to refine the trajectory obtained from the inertial unit and to locate the bottom. Although the manual recommends using the DVL 1 to 30 meters above the bottom, experience in the Mediterranean Sea, in an area with few reflectors except near the surface in the plume zone, with mud on the bottom and the presence of fish groups, shows that the maximum altitude can be halved under these conditions. The routes chosen must therefore take into account the real range of the DVL. ⚙️

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the added value of observing the coastal ocean, hence the river plumes, using micro-AUVs. They are able to catch the oceanic variability at small scale

and provide an interesting spatialization, easy-to-use, tool. However, more could be done with these systems. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles are more stable platforms for conducting velocity transects and are more immune to the artifacts introduced by surface chop and near-surface bubbles that typically contaminate ship-based measurements. The next step will therefore be to use the YUCO with a DVL-ADCP capability, by changing the DVL for a DVL-ADCP as the Nortek Nucleus1000. Indeed, [5] deployed a coastal Iver2

AUV equipped with a 1MHz SonTek ADCP to perform velocity measurements in the coastal area around the OBSEA cabled observatory, off Catalonia, in the western Mediterranean. To the first order, the velocities measured by the DVL compared well with a stationary ADCP, and sawtooth types of surveys were proved to be as accurate as constant depth ones. Recent micro-AUVs include systems equipped with a USBL for a better underwater positioning. Addition of the USBL to the DVL positioning would improve the velocity measurements and would be needed if the micro-AUV navigates in specific environments like under a rigid wall or ice. Deployments dedicated to the study of extreme events should include a recovery system, where a micro-AUV localization on the surface is provided after its dive for a few days, so that the AUV could be recovered by boat after bad sea conditions. In order to sample the frontal structures associated with river plumes, a pack of AUVs could be used simultaneously to capture the variability of the processes at play, for which micro-AUVs represent an interesting choice, as their price is affordable. In order to provide the spatial coverage needed by an augmented observatory, and in the framework of land-sea continuum studies, deployments of micro-AUVs in coastal areas associated with glider deployments in deeper areas over the shelf are foreseen. In that context, the development of small resident AUVs around existing observing fixed stations is an avenue worth exploring.

This study was also conducted as part of the RiOMar project from the national Ocean and Climate research priority program (PPR Oc´ean et Climat, funded by the French National Research Agency – ANR-22-POCE-0006), as well as the State-Region Plan Contract ObsOcean – ROECILICO.

Thanks to Pairaud Ivane, Petton Sébastien, Sellet Hugo, Helleringer Cecile, Le Bihan Caroline, and Charria Guillaume for writing this article.

References

[1]E. Galerne, ”Epaulard ROV used in NOAA polymetallic sulfide research”,

Sea Technol., vol. 24, 1983, pp. 40–42.

[2] R. B. Wynn, V. A. I. Huvenne, T. P. Le Bas, B. J. Murton, D.

P. Connelly, B. J. Bett, et al., ”Autonomous Underwater Vehicles

(AUVs): Their past, present and future contributions to the advancement

of marine geoscience”, Mar. Geol., vol. 352, 2014, pp. 451–468,

DOI:10.1016/j.margeo.2014.03.012.

[3] H. Kumagai, S. Tsukioka, H. Yamamoto, T. Tsuji, K. Shitashima, M.

Asada et al., ”Hydrothermal plumes imaged byhigh-resolution side-scan

sonar on a cruising auv, Urashima”, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., vol.

11, 2010, DOI:10.1029/2010GC003337.

[4] S. McPhail, P. Stevenson, M. Pebody, M. Furlong, J. Perrett and T.

Lebas, ”Challenges of using an auv to find and map hydrothermalvent

sites in deep and rugged terrains”, IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater

Vehicles, 2010, pp. 1–8, DOI:10.1109/AUV.2010.5779656.

[5] S. Cusi, P. Rodriguez, N. Pujol, I. Pairaud, M. Nogueras, J. Antonijuan et

al., ”Evaluation of AUV-Borne ADCP Measurements in Different Navigation

Modes” , Proc. OCEANS’17 MTS/IEE Conference, Aberdeen,

Scotland, June 2017, pp. 1–8, DOI:10.1109/OCEANSE.2017.8084688.

[6] R. Semp´er´e, C. Guieu, I. Pairaud and X. Durrieu de Madron, ”Preface of

special issue of MERMEX project: Recent advances in the oceanography

of the Mediterranean Sea”, Prog. Oceanogr., vol. 163, 2018, pp. 1–6,

DOI:10.1016/j.pocean.2018.03.014.

[7] R. Verney, ”BATHY DELTA RHONE E cruise, RV L’Europe”, 2021,

DOI:10.17600/18001627

[8] P. Farcy, D. Durand, G. Charria, S.J. Painting, T. Tamminem, K.

Collingridge et al., ”Toward a European coastal observing network to

provide better answers to science and to societal challenges; the JERICO

research infrastructure”, Front. Mar. Sci., vol. 6 (A529), 2019, pp. 1–13,

DOI:10.3389/fmars.2019.00529